Our aesthetic choices as writers often happen under the radar; we are only dimly aware we are making them, even as we draw upon their elusive power. Aesthetics here means a judgement of what is artistically valid and pleasing – and, crucially, what is the right feel, mood, approach and structure for the work we are writing. Amit Chaudhuri, my colleague at the UEA, recently delivered the first of a duo of inspirational and wide-ranging masterclasses to our current cohort of MA prose fiction students on this topic.

Our aesthetic choices as writers often happen under the radar; we are only dimly aware we are making them, even as we draw upon their elusive power. Aesthetics here means a judgement of what is artistically valid and pleasing – and, crucially, what is the right feel, mood, approach and structure for the work we are writing. Amit Chaudhuri, my colleague at the UEA, recently delivered the first of a duo of inspirational and wide-ranging masterclasses to our current cohort of MA prose fiction students on this topic.

Chaudhuri began his discussion with the admission that his earliest preoccupation as a writer was a sense of belatedness. ‘The historical moment I wanted to occupy has passed,’ he said. What he had wanted to do as a writer had already been done. ‘Our historical moment dictates our ability to write about great issues.’

It can be difficult to define one’s historical moment. Often we have a firmer grip on where we are not (in a time of war and upheaval or collapse) than where we are. Where we have arrived on the plane of space-time as a writer determines everything, including whether you write at all. Imagine Solzhenitsyn growing up in suburban Michigan. Or Richard Ford coming to consciousness in revolutionary Madagascar. Our provenance, selfhood and territory as writers are intertwined. Flannery O’Connor put it with characteristic brevity: ‘If you’re going to write, you’d better have somewhere to come from.’

But territory, in fiction, is not so much terrestrial as subject. It is what are you driven to write about. In an interview for New Writing Net Stephen Kelman, author of the much-lauded first novel Pigeon English, comments, ‘For me, the commitment to write a book is such an important one that I could only make it for a story that I feel I absolutely have to tell. The things that attract me to a story are very personal and instinctive. My territory as a writer is mapped by my life outside of my work, it’s not so much a conscious choice as a reaction to my individual experience of living.’

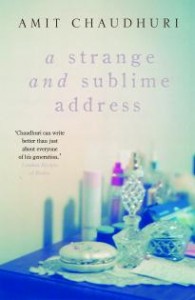

For Chaudhuri, he needed to somehow supercede the power of the past, whether a fragmentary (modernism) or a sacred (Victorian and Edwardian literature) version. One way to write about the past is to write about the present; the past is forged in an arena of continuous present tense. For his first novel, A Strange and Sublime Address (1991) he developed an aesthetic of the dimension of the present moment.

Although where is the present moment located? Neuroscience tells us that the present moment lasts exactly three seconds; this is the maximum duration the human brain can conceive of being in the ‘now’. After three seconds, another ‘now’ must follow. We live in three-second parcels. But focussing fiction’s emotional and interpretive intensity of the moment produces a collusion with eternity, by prolonging our sense of experiential depth, even if we are mere readers and not participants in the unfolding drama of the novel. Fiction turns information into experience, and experience happens for human beings in time.

Another aesthetic Chaudhuri found himself drawn to doubles as a narrative structure and device: ‘Looking at each of my books, I found that there was a visit. In each of them the characters decamp, and go somewhere else.’ A visit is distinct from a journey, although it often requires the latter. In A Strange and Sublime Address, the child Sandeep is living in Bombay high-rise; in the novel he makes two visits to his family in Calcutta. The novel is told in discrete episodes comprised of moments, which explore the mysterious occulted dimensions of the now. This is essentially a phenomenological approach, where our subjective experience of the moment is the sum total of the structures of consciousness, and indeed weaves the fabric of what we call reality. In these extended hiatuses, his characters come to understandings that would never be possible if they had stayed at home.

So how do you find your aesthetic as a writer? Through making choices. Writers, particularly novelists, have to choose: from what perspective will they tell the story, how will they get the narrative to triumph over the lure of inertia and gain a pleasing pacing, how much time will pass within the novel, will it be told looking over the character’s shoulder, in a past tense of record, or in the ever-emergent present tense?

These might not be aesthetic choices, strictly speaking, rather they are technical decisions. To arrive at a true aesthetic requires an emotional journey. An aesthetic is closer to a world-view, a privileging of one aspect of reality over another. Much of the time I feel that the fictional work makes these choices for itself, and our job as writers is to interpret what the fictional work – whether a short story, novella or novel – wants to be. This presents a paradox, of course: we have to interpret the desires of a text which does not yet exist, because we have not yet created it.

Chaudhuri, in his first novel at least, found himself drawn to the propensities of the ordinary, the commonplace, rather than the grand picaresque narrative in vogue in writing from India (at least those Indian writers published abroad) at the time. Ordinary moments and commonplace happenings form our actual meridian of time. This is how time moves forward, for all of us, yet this actual quanta of our time on the planet remains not only unexamined but neglected in favour of grand narratives, of the much-anticipated dramatic moments, the turning points and events. Chaudhuri decided to celebrate place over character, and discovered that place might be character, just as the quotidian – the small stuff of every day life – might, on examination, be so much more strange and revelatory than any event.

Stillness and animation; the transcendental capacities of the single moment; the visit; the sentence and phrase as the basis for and heart of fiction; a moment of limited duration compelled into immortality through fictional examination; the privileging of the invisible over the visible, the intangible over the tangible – a territory has begun to cohere.

The subtext of Chadhuri’s talk was a question to us in the audience, writers all: what is your aesthetic, your territory? I’m not sure it is possible to define your own aesthetic, as a writer. Or at least not immediately or while in the process of creating it. The project benefits from Chaudhuri’s critical acumen, his experience as a writer of fiction and non fiction but also as an experienced literary critic. And retrospect, perhaps.

For me the process of choosing the right aesthetic is akin to listening out for a slim frequency, a music even, trapped between louder currents of narrative exigencies and even anxiety. The sound is dim at first, but crescendos when it knows it has been detected. Soon it fills your ears. Aesthetic choices in the moment of their making remain slippery, elusive, but necessary. Perhaps that is all we truly know.

Two years I’ve been hunting down my aesthetic, the place and possibility of what I might write. I call it keening to the ether. When I started I had no idea the process would take so long, be so mysterious, involve so many decisions that make themselves without my knowing. I must lay in wait though, stalk them even, as they pussyfoot round my consciousness.

Thanks Jean. I learn and gain hope from reading this. Your writing and sharing helps me keep at it.