An extract from Ilona Bushell’s biography of Margery Allingham, The Beckoning Land.

A J Gregory, “A Map of Mystery Mile” in Margery Allingham, Mystery Mile

(repr., Aylesbury and London: Penguin, 1952)

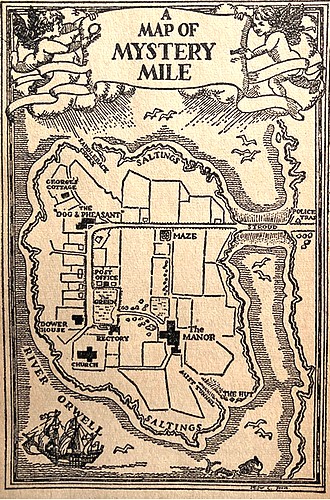

The first book by Margery Allingham I ever bought was Mystery Mile. It is a little Penguin classic with a green jacket, identifying it in the genre of ‘crime fiction’. Across the front is a white strip containing the title and the black and white bird stands underneath looking to one side. On the third page, directly after the table of contents and before the first chapter, is a map. At the top are two cherubs holding an old-fashioned ribbon banner displaying the title, ‘A Map of Mystery Mile’. Below the little fat angels, an island takes up the majority of the space. Though small, it shows some details — a Manor, a Dower House, church and rectory, a smattering of cottages, The Dog and Pheasant Pub, and a post office. There is a single road running across the island and out towards the mainland over a narrow causeway marked ‘Stroud’. The coast is intricately drawn, the fjord-like shapes labelled ‘Saltings’. In the water surrounding the little island, a sixteenth-century ship sails past the words ‘River Orwell’ and ten gulls fly about the page. In the bottom right, a sea monster pokes its head out from the depths.

There is something rather extraordinary about opening a book and finding a map of an imaginary place. It speaks of fantasy, adventure, and things not quite real. In fact, maps themselves are hyper-real. Medieval and early modern Mappae Mundi show the world the way it existed in the mind of the mapmaker rather than how it appears from above. They merge the known with the unknown, the charted with the uncharted. Monsters, exotic creatures and unusual peoples populate the edges of these early maps, while Rome sits at the centre above Hell and beneath Heaven.

Even modern maps represent a view of the world that is not really how it exists. Just as Medieval maps had Christian Rome at their centre, so their modern counterparts paint North America and Europe in the middle and disproportionately large. We have all become so used to this worldview that when we look at different versions, we find them uncomfortable. The first time I saw the Gall-Peters projection — a map that shows a less western-centric view — I saw the world flattened and distorted, melting down into the South Pole like a Dali painting.

The illustrator of ‘The Map of Mystery Mile’ was A. J. Gregory, a close friend of the author, known affectionately as Grog. He had been present all through the creation of this second instalment of what would become the famous Albert Campion collection. He had also been present when Campion’s character was invented. In 1928, Margery Allingham had been married to the artist, Philip Youngman Carter – Pip – for just a year. They were living, together with Grog in a minute flat in Holborn. Pip made his living designing book jackets for various authors while Margery made hers translating silent films into short stories for The Girls’ Cinema. The summer came and the small space and the rush of London were too much. The little group wanted a holiday. Fortunately, Allingham’s parents lived in the large Old Vicarage at Letheringham in Suffolk and agreed to swap for a short time.

While in Suffolk, Margery — who had already written two books — began work on a third. The Crime at Black Dudley is a dramatic story set in a vast ancestral seat. It is full of spies and lies and cupboards concealing passageways. Writing it was a joint effort. Margery would dictate as Pip scribbled down notes and together they pruned out words, thought up names, and giggled their way through the novel. When the story was ready, Grog typed it up. It was a system that worked and the group repeated it two years later. In 1930, Mystery Mile was published, co-written, as before, by the three in Letheringham.

This time, Grog had his own addition. The map is typical of those found in fantasy novels, in the front of Lord of the Rings, or books by Robert Louis Stevenson. Indeed, the one in the opening pages of Treasure Island features an almost identical boat and sea monster. Such maps are throwbacks to the times when cartographers were at once explorers and fantasists. They recall a time where sections of the world were dark, shadowy unknowns. But they also invite readers into worlds imagined into existence by the author, plunging them into a place of fiction. The world of Mystery Mile, therefore, is a fantasy one, one of adventure, romance, intrigue and fear.

But ‘The Map of Mystery Mile’ is also steeped in realism. It captures the sense of any East Anglian coastal village in the early 1930s — the sea never far off, saltmarsh on the horizon, few shops, a smattering of farmers, a run-down manor. The island is also highly reminiscent of Mersea, the large island between the Blackwater and the Colne, surrounded by mud and connected to the mainland with a causeway with a name only slightly different from its fictional one : the Strood. Grog’s map, however, makes it clear to any reader that Mystery Mile is not Mersea. That real island is much bigger, with far more inhabitants — and no sea monsters. In any case, it is well-known that Mersea is in the Blackwater while this Mystery Mile is in the Orwell, miles away in the foreign county of Suffolk.

When I first came across Margery Allingham at the age of eleven, I knew nothing about where she lived or where she set her books. I knew that my mother had bought an audiobook of an Albert Campion novel to listen to on long drives to work and I knew that I did not enjoy it. I found the stories too complicated, too involved. I wanted a green-jacketed classic crime novel, a puzzle solved by a brilliant detective. It was not until I discovered that Allingham had lived and worked in Essex and that most of her books took place in the villages where I had grown up, that I became more interested. I was no longer listening for a mystery to be solved. I was not listening for whodunnit. I was listening for home.

Slowly, I found it. It was different — villages were obscured with false names and slight technical alterations — but it was a landscape I knew. I began to map out the places I recognised and, gradually, a parallel landscape began to emerge, the landscape described affectionately by her biographer, Julia Jones as ‘Margeland’. It was a landscape where names like Ipswich and Colchester mingled with imagined places of Redding Knights and Kepesake.

In its mingled realism and fantasy, the map in the front of Mystery Mile is the beginning of this imagined Essex that builds and develops throughout Allingham’s work. Essex itself is a place of mingled realism and fantasy; it is a caricature; it is a particular voice, a particular type of woman; it is commuter trains and run-down seaside towns. Yet, at the same time, it is a place of exceptional depth. Essex has unique and revered physical landscape and wildlife. It has a complicated and captivating social background, rich folklore, deeply held beliefs, long history. Reading Allingham’s Essex novels is one way to read this landscape and gain a deeper understanding of how it changed through the years.

Yet Allingham’s work is not only a reflection of a landscape but it has become part of it. Spend some time in the small coastal villages of Layer Breton and Tolleshunt D’Arcy and you will find her old homes, each bearing a blue plaque. You will see her books in local bookshops. Further inland, you will find a collection of cottages in Chappel named after the author. Near Tiptree, you might even stumble across Margery Allingham Close. The author has written herself into the landscape – perhaps not in the most Romantic sense – but she is there all the same and she is remembered as a great East Anglian writer. For me, she is the great East Anglian writer, who tells the story of Essex like no other. The green jackets are just an extra.